ΣΧΟΛΙΟ ΙΣΤΟΛΟΓΙΟΥ : Σχετικό και αυτό . Όλο αυτό έχει σχέση με γεννήσεις και με θανάτους ηλίων...διότι αυτό που δεν ξέρουν οι επιστήμονες ακόμα, είναι ότι ο γαλαξίας μας η κάποιος άλλος όπως της Ανδρομέδας , τρώει έναν άλλο γαλαξία.... για να μπορέσει να γεννήσει νέους Ήλιους. Είναι ακριβώς όπως ο άνθρωπος και ο γαλαξίας....πρέπει να τραφεί να "φάει" για να μπορέσει να αναπτυχθεί να μεγαλώσει.....και να δημιουργήσει νέα "κύτταρα" η 'Ήλιους.

This is certainly true of the Andromeda Galaxy (aka. M31, Earth's closest neighbor) which has a massive and nearly-invisible halo of stars that is larger than the galaxy itself.

For some time, scientists believed that this halo was the result of hundreds of smaller mergers. But thanks to a new study by a team of researchers at the University of Michigan, it now appears that Andromeda's halo is the result of it cannibalizing a massive galaxy some 2 billion years ago.

Studying the remains of this galaxy will help astronomers understand how disk galaxies (like the Milky Way) evolve and survive large mergers.

The study, titled 'The Andromeda galaxy's most important merger about 2 billion years ago as M32's likely progenitor', recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature.

The study was conducted by Richard D'Souza, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Michigan and the Vatican Observatory; and Eric F. Bell, the Arthur F. Thurnau Professor at the University of Michigan.

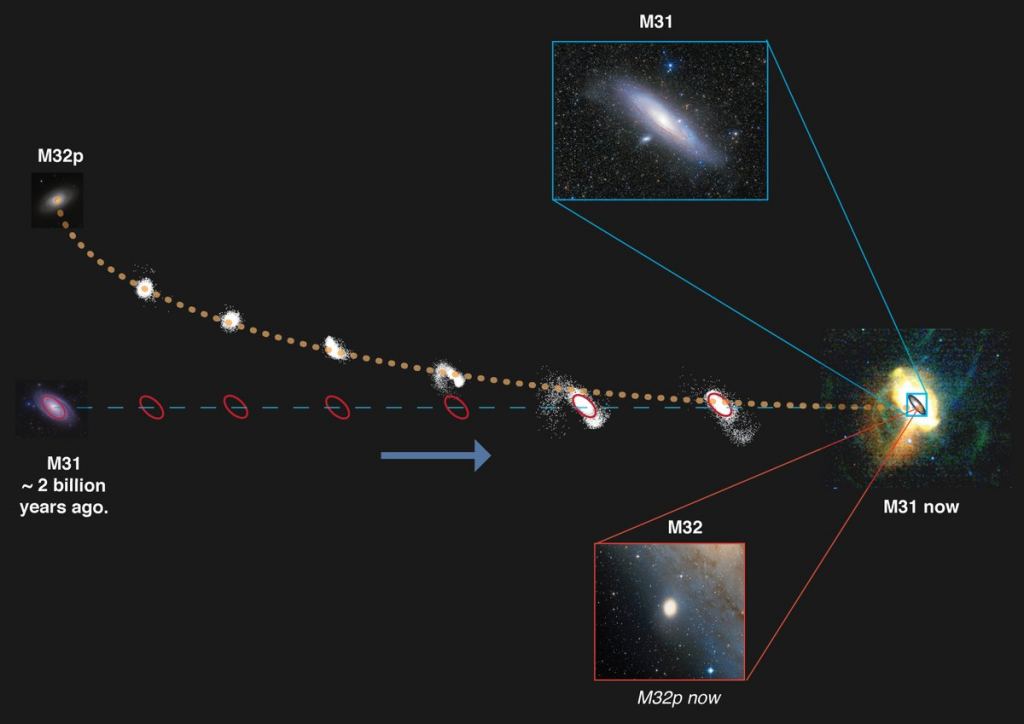

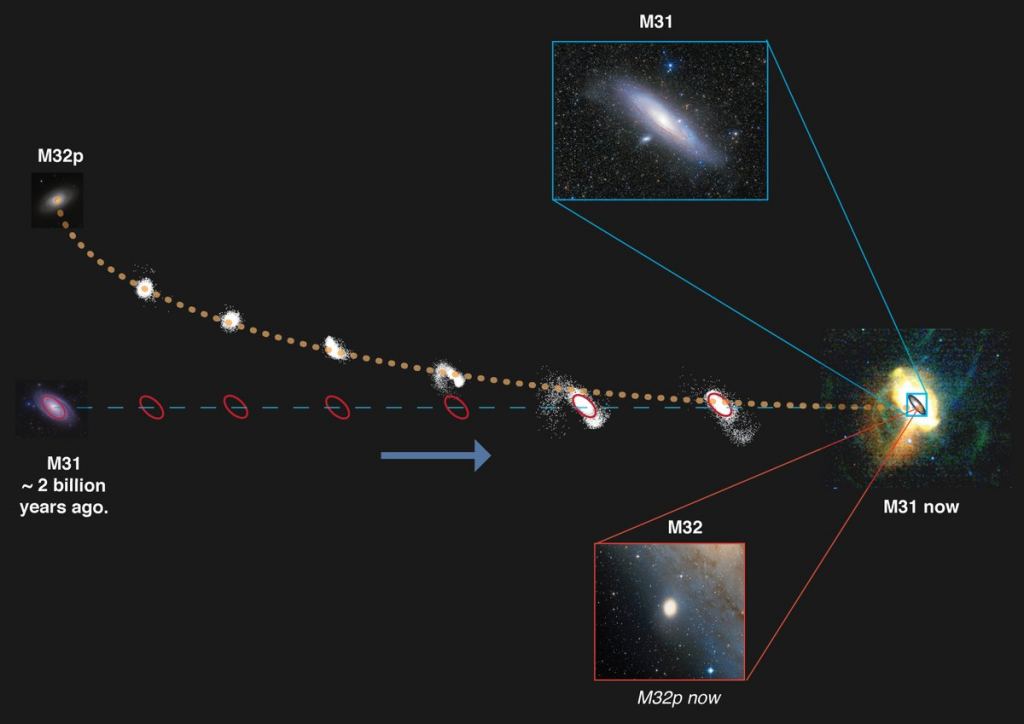

Andromeda shreds M32p resulting in M32 and a halo of stars. ( Richard D'Souza/ASS/IP/Wei-Hoo Wang)

Andromeda shreds M32p resulting in M32 and a halo of stars. ( Richard D'Souza/ASS/IP/Wei-Hoo Wang)

Using computer models, Richard D'Souza and Eric Bell were able to piece together how a once-massive galaxy (named M32p) disrupted and eventually came to merge with Andromeda.

From their simulations, they determined that M32p was at least 20 times larger than any galaxy that has merged with the Milky Way over the course of its lifetime.

M32p would have therefore been the third-largest member of the Local Group of galaxies, after the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies, and was therefore something of a "long-lost sibling".

However, their simulations also indicated that many smaller companion galaxies merged with Andromeda over time. But for the past, Andromeda's halo is the result of a single massive merger.

As D'Souza explained in a recent Michigan News press statement:

According to their study, D'Souza and Bell believe that M32 is the surviving center of M32p, which is what remained after its spiral arms were stripped away.

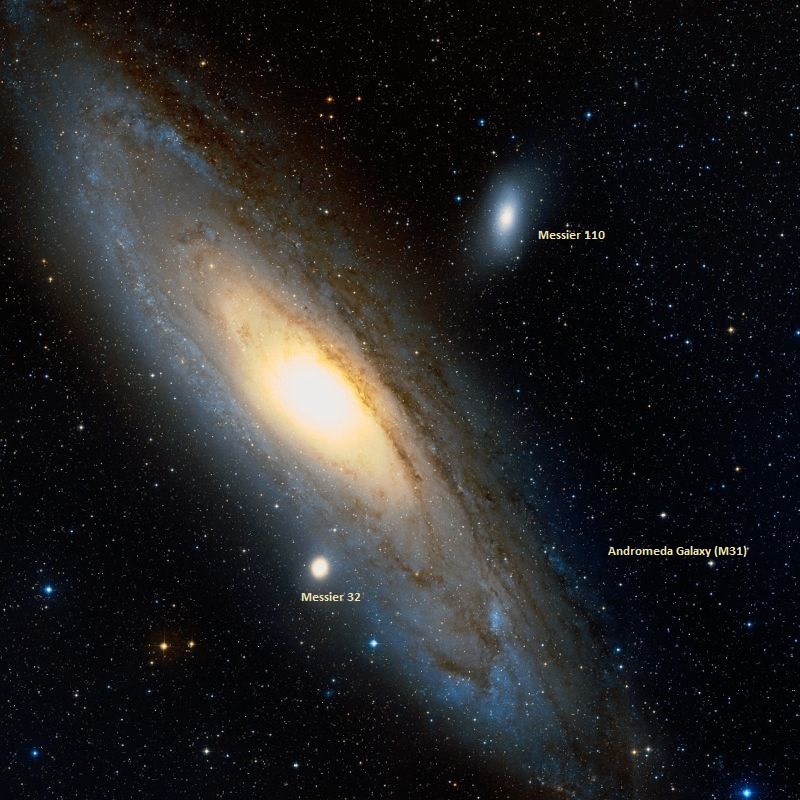

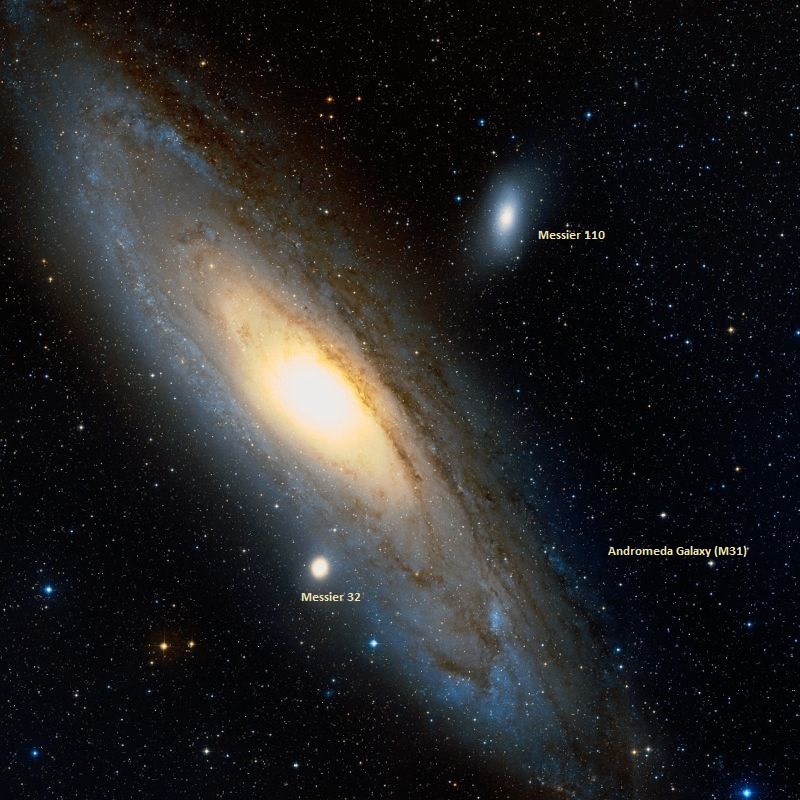

Andromeda Galaxy, M31, with remnant of M32p now M32 (Wikisky)

Andromeda Galaxy, M31, with remnant of M32p now M32 (Wikisky)

"M32 is a weirdo," said Bell. "While it looks like a compact example of an old, elliptical galaxy, it actually has lots of young stars. It's one of the most compact galaxies in the universe. There isn't another galaxy like it."

According to D'Souza and Bell, this study may also alter the traditional understanding of how galaxies evolve. In astronomy, conventional wisdom says that large interactions would destroy disk galaxies and form elliptical galaxies.

But if Andromeda did indeed survive an impact with a massive galaxy, it would indicate that this is not the case. The timing of the merger may also explain recent research findings which indicated that 2 billion years ago, the disk of the Andromeda galaxy thickened, leading to a burst in star formation.

As Bell explained:

This knowledge will certainly come in handy when it comes to determining what will happen to our galaxy when it merges with Andromeda in a few billion years.

ΠΗΓΗ

"Μία μοσχαράκι στο 14" χαχα

Scientists have long understood that in the course of cosmic evolution, galaxies become larger by consuming smaller galaxies. The evidence of this can be seen by observing galactic halos, where the stars of cannibalized galaxies still remain.This is certainly true of the Andromeda Galaxy (aka. M31, Earth's closest neighbor) which has a massive and nearly-invisible halo of stars that is larger than the galaxy itself.

For some time, scientists believed that this halo was the result of hundreds of smaller mergers. But thanks to a new study by a team of researchers at the University of Michigan, it now appears that Andromeda's halo is the result of it cannibalizing a massive galaxy some 2 billion years ago.

Studying the remains of this galaxy will help astronomers understand how disk galaxies (like the Milky Way) evolve and survive large mergers.

The study, titled 'The Andromeda galaxy's most important merger about 2 billion years ago as M32's likely progenitor', recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature.

The study was conducted by Richard D'Souza, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Michigan and the Vatican Observatory; and Eric F. Bell, the Arthur F. Thurnau Professor at the University of Michigan.

Andromeda shreds M32p resulting in M32 and a halo of stars. ( Richard D'Souza/ASS/IP/Wei-Hoo Wang)

Andromeda shreds M32p resulting in M32 and a halo of stars. ( Richard D'Souza/ASS/IP/Wei-Hoo Wang)Using computer models, Richard D'Souza and Eric Bell were able to piece together how a once-massive galaxy (named M32p) disrupted and eventually came to merge with Andromeda.

From their simulations, they determined that M32p was at least 20 times larger than any galaxy that has merged with the Milky Way over the course of its lifetime.

M32p would have therefore been the third-largest member of the Local Group of galaxies, after the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies, and was therefore something of a "long-lost sibling".

However, their simulations also indicated that many smaller companion galaxies merged with Andromeda over time. But for the past, Andromeda's halo is the result of a single massive merger.

As D'Souza explained in a recent Michigan News press statement:

"It was a 'eureka' moment. We realized we could use this information of Andromeda's outer stellar halo to infer the properties of the largest of these shredded galaxies. Astronomers have been studying the Local Group - the Milky Way, Andromeda and their companions - for so long.This study will not only help astronomers understand how galaxies like the Milky Way and Andromeda grew through mergers, it might also shed light on a long-standing mystery – which is how Andromeda's satellite galaxy (M32) formed.

It was shocking to realize that the Milky Way had a large sibling, and we never knew about it."

According to their study, D'Souza and Bell believe that M32 is the surviving center of M32p, which is what remained after its spiral arms were stripped away.

Andromeda Galaxy, M31, with remnant of M32p now M32 (Wikisky)

Andromeda Galaxy, M31, with remnant of M32p now M32 (Wikisky)"M32 is a weirdo," said Bell. "While it looks like a compact example of an old, elliptical galaxy, it actually has lots of young stars. It's one of the most compact galaxies in the universe. There isn't another galaxy like it."

According to D'Souza and Bell, this study may also alter the traditional understanding of how galaxies evolve. In astronomy, conventional wisdom says that large interactions would destroy disk galaxies and form elliptical galaxies.

But if Andromeda did indeed survive an impact with a massive galaxy, it would indicate that this is not the case. The timing of the merger may also explain recent research findings which indicated that 2 billion years ago, the disk of the Andromeda galaxy thickened, leading to a burst in star formation.

As Bell explained:

"The Andromeda Galaxy, with a spectacular burst of star formation, would have looked so different 2 billion years ago. When I was at graduate school, I was told that understanding how the Andromeda Galaxy and its satellite galaxy M32 formed would go a long way towards unraveling the mysteries of galaxy formation."In the end, this method could also be used to study other galaxies and determine which were the most massive mergers they underwent. This could allow scientists to better understand the complicated process that drives galaxy growth and how mergers affect galaxies.

This knowledge will certainly come in handy when it comes to determining what will happen to our galaxy when it merges with Andromeda in a few billion years.

ΠΗΓΗ

1 σχόλιο:

το προβλημα ειναι να τρωει σαν τον Παγκαλο και τον Βενιζελο

Δημοσίευση σχολίου